의 기원 중국말 요리 천년을 거슬러 올라갈 수 있습니다. 중국 요리는 지역에 따라 매우 다양하며, 중국인조차도 다른 지역의 요리가 그들에게 완전히 이국적이라고 생각하는 것은 드문 일이 아닙니다. 북부 중국인은 광둥 요리가 토마토와 함께 볶은 계란으로만 구성되어 있다고 생각할 수 있지만 남부인은 중국 북부에서 제공되는 만두의 크기에 놀랄 수 있습니다.

이해하다

| “ | 민간인은 왕의 통치의 기초이고 음식은 민간인의 삶의 기초입니다. | ” |

—반구, 한서, 43권 | ||

을 통하여 제국 중국, 중국 문화는 오늘날과 같은 나라에 영향을 미쳤습니다. 몽골리아 과 베트남. 중국 요리는 오랫동안 다음과 같은 다른 아시아 국가에서 명성을 얻었습니다. 대한민국 과 일본.

현대에 이르러 디아스포라 중국인들은 중국 요리를 세계의 더 멀리 떨어진 지역으로 퍼뜨렸습니다. 즉, 이것의 대부분은 현지 상황에 맞게 조정되었으므로 중국에서는 찾을 수 없거나 원래 중국어 버전에서 크게 수정 된 요리를 해외 화교 커뮤니티에서 종종 찾을 수 있습니다. 말레이시아, 태국, 베트남 과 싱가포르 특히 중국인 공동체의 오랜 역사와 현지 전통 재료의 맛과 조리법으로 인해 이러한 요리를 맛볼 수 있는 훌륭한 장소입니다. 반대로, 화교로 돌아온 것은 조국의 요리계에도 영향을 미쳤는데, 아마도 가장 두드러지게 나타났을 것입니다. 광동, 복건 과 하이난.

서구 국가의 많은 도시에는 중국인 거리 지역, 심지어 작은 마을에도 종종 중국 식당이 몇 군데 있습니다. 이 장소는 항상 주로 광둥 음식을 먹었지만 다른 스타일이 더 보편화되었습니다.

중국 요리는 단순하지만 푸짐한 길거리 음식부터 가장 독점적인 재료만을 사용하여 가격에 맞는 최고급 고급 식사에 이르기까지 다양합니다. 홍콩 일반적으로 중국의 세계 주요 중심지로 간주됩니다. 고급 레스토랑, 그러나 싱가포르 과 타이베이 어느 쪽도 주저하지 않으며 중국 본토 도시의 상하이 과 베이징 느리지만 확실히 따라잡고 있습니다.

식사 시간 중국에서는 유럽 국가보다 미국 식사 시간에 더 가깝습니다. 아침 식사는 일반적으로 07:00에서 09:00 사이이며 국수, 찐빵, 죽, 튀긴 페이스트리, 두유, 야채 또는 만두 등이 포함됩니다. 점심 피크 시간은 12:00-13:00이고 저녁은 17:30-19:30 정도입니다.

지역 요리

중국 요리는 거주하는 국가에 따라 크게 다릅니다. "四大菜系"는 쓰촨 (천), 산동 (루), 광동 (광둥어/위에), 강소 (화이양) 요리 및 기타 지역에도 고유한 스타일이 있으며 다음과 같은 소수 민족 지역의 요리 전통이 현저하게 다릅니다. 티베트 과 신장.

지역 특산물을 맛보기란 여간 어려운 일이 아니다. 중국 당신이 그들의 출신 지역에서 멀리 떨어져 있더라도 - 사천 말라 (麻辣) 맵고 매운 음식은 예를 들어 간판 광고처럼 곳곳에서 볼 수 있습니다. 란저우 국수(兰州拉面, Lánzhōu lāmiàn). 마찬가지로 북경오리(北京烤鸭)는 표면적으로는 지역 특산품이지만 베이징, 그것은 또한 많은 광동 레스토랑에서 널리 사용할 수 있습니다.

- 베이징 (京菜 징 카이 ): 가정식 국수 및 바오지 북경오리(北京烤鸭), 包子빵 베이징 카오야), 볶음 소스 국수 (炸酱面) 장미안), 양배추 요리, 훌륭한 피클. 맛있고 만족스러울 수 있습니다.

- 황실(宫廷菜) 궁팅까이): 서태후가 유명해진 청나라 후기 음식은 베이징의 고급 전문 레스토랑에서 맛볼 수 있습니다. 이 요리는 사슴 고기와 같은 만주 국경 음식의 요소와 낙타 발, 상어 지느러미, 새 둥지와 같은 독특한 이국적인 음식을 결합합니다.

- 광둥어 / 광저우 / 홍콩 (广东菜 광동차이, 粤菜 위에까이): 대부분의 서양 방문자가 이미 친숙한 스타일입니다(현지화된 형식이기는 하지만). 너무 맵지 않고 신선하게 조리된 재료와 해산물에 중점을 둡니다. 즉, 정통 광둥 요리는 또한 다양한 재료 측면에서 중국에서 가장 모험심이 강한 요리 중 하나입니다. 광둥 요리는 식용으로 간주되는 것에 대한 매우 광범위한 정의로 중국인들 사이에서도 유명하기 때문입니다.

- 딤섬(点心) 디엔신 북경어로, 딤삼 광둥어로) 아침이나 점심에 주로 먹는 작은 간식이 하이라이트입니다.

- 구운 고기(烧味) 샤오웨이 북경어로, 시우메이 烧鸭과 같이 서부 차이나타운에서 인기 있는 일부 요리를 포함하는 광둥 요리에서도 인기가 있습니다. 샤오야 북경어로, 시우아프 간장 치킨(豉油鸡) 차유지 북경어로, 시야우가이 광동어로 叉烧 차샤오 북경어로, 차시우 광동어)와 바삭한 삼겹살(烧肉) 샤오루우 북경어로, 시유크 광둥어로).

- 훈육(腊味) 라웨이 북경어로, 라프메이 腊肠)은 광둥 요리의 또 다른 특산품으로 중국식 소시지(腊肠)를 포함합니다. 라창 북경어로, 라압청 간소시지(膶肠) 룽창 북경어로, 연청 광둥어로) 및 보존 오리(腊鸭) 라야 북경어로, 라아프아프 광둥어로).腊味煲仔饭(腊味煲仔饭)을 육수에 담가서 먹는 것이 일반적이다. làwèi bāozǎi fàn 북경어로, laahpméi boujai faahn 광둥어로).

- 죽(粥) 주 북경어로, 죽 in Cantonese)는 광둥 요리에서도 인기가 있습니다. 광둥식 콘지는 쌀알이 더 이상 보이지 않을 때까지 쌀을 삶고 고기, 해산물 또는 내장과 같은 다른 재료를 쌀과 함께 넣어 콘지의 풍미를 더합니다.

- 화이양(淮揚菜) 화이양 카이): 요리 상하이, 강소 과 저장성, 북부와 남부 중국 요리 스타일의 좋은 혼합으로 간주됩니다. 가장 유명한 요리는 샤오롱바오 (小笼包 샤오롱바오)와 부추 만두(韭菜饺子) Jiǔcài Jiǎozi). 다른 시그니처 메뉴로는 삼겹살 찜(红烧肉)이 있습니다. 홍 샤오루)과 탕수육(糖醋排骨) 탕꾸파이고). 설탕은 종종 튀긴 요리에 첨가되어 달콤한 맛을냅니다. 상하이 요리가 종종 이 스타일의 대표자로 여겨지지만 항저우, 쑤저우, 난징과 같은 인근 도시의 요리에는 고유한 요리와 맛이 있으며 시도해 볼 가치가 있습니다.

- 쓰촨 (川菜 추안 카이): 뜨겁고 매운 것으로 유명합니다. 너무 매워서 입이 떡벌어진다는 속담이 있다. 그러나 모든 요리가 살아있는 고추로 만들어지는 것은 아닙니다. 마비된 감각은 실제로 쓰촨 후추(花椒)에서 비롯됩니다. 화자오). 쓰촨성 외 지역에서 널리 구할 수 있으며 충칭 원산이기도 합니다. 쓰촨이나 충칭 밖에서 진정한 쓰촨 음식을 먹고 싶다면 이주 노동자가 많은 동네에서 쓰촨 요리의 특징을 지닌 작은 식당을 찾으세요. 이들은 유비쿼터스 고급 사천 레스토랑보다 훨씬 저렴하고 종종 더 나은 경향이 있습니다.

- 후난 (湖南菜 후난 카이, 湘菜 샹차이): Xiangjiang 지역, Dongting 호수 및 서부 후난성 요리. 어떤 면에서는 사천 요리와 유사하게 서양식 의미에서 실제로 "더 맵게" 될 수 있습니다.

- 潮州菜 테오주(潮州菜) 차오저우 카이): 에서 유래 차오산 그럼에도 불구하고 대부분의 동남아시아와 홍콩 중국인들에게 친숙할 독특한 스타일입니다. 유명한 요리로는 오리찜(卤鸭)이 있습니다. 라야), 참마 페이스트 디저트(芋泥) 유니)와 생선구이(鱼丸) 유완).

- 죽(粥) 주 북경어로 糜 무에5 in Teochew)는 Teochew 요리의 편안한 요리입니다. 광동어 버전과 달리 테오츄 버전은 쌀알을 그대로 둡니다. 테오츄죽은 보통 다른 짭짤한 요리와 함께 일반 요리로 제공되지만, 터츄 죽에는 종종 쌀을 생선 국물에 삶아 생선 조각을 넣어 끓입니다.

- 객가(客家菜) 케지아 카이): 중국 남부의 여러 지역에 퍼진 Hakka 사람들의 요리. 보존 고기와 야채에 중점을 둡니다. 유명한 요리로는 두부(酿豆腐)가 있습니다. 니앙두우피, 속을 채운 고기는 물론), 속을 채운 비터멜론(酿苦瓜) 니앙카과, 또한 고기로 속을 채움), 절인 겨자채 돼지고기(梅菜扣肉) méicài kòuròu), 돼지고기 토란(芋头扣肉) yùtóu kòuròu), 닭고기 소금구이(盐焗鸡 yánjújī)와 차(擂茶) 레이 차).

- 복건 (福建菜 푸젠 까이, 闽菜 만까이): 연안 및 하구 수로의 재료를 주로 사용합니다. 복건 요리는 적어도 세 가지 독특한 요리로 나눌 수 있습니다. 남복건성 요리, 푸저우 요리, 그리고 서복건 요리.

- 죽(粥) 주 북경어로 糜 있다 Minnan)은 남부 푸젠에서 인기 있는 요리입니다. Teochew 버전과 비슷하지만 일반적으로 고구마 조각으로 요리됩니다. 아침 식사의 단골 메뉴인 대만에서도 매우 인기가 있습니다.

- 구이저우 (贵州菜 구이저우 카이, 黔菜 첸 카이): 쓰촨 요리와 샹 요리의 요소를 결합하여 매운맛, 후추맛, 신맛을 자유롭게 사용합니다. 특이한 체르겐 (折耳根 Zhē'ěrgēn지역 뿌리 채소인 )은 많은 요리에 틀림없는 새콤한 고추 풍미를 더합니다. 신어전골(酸汤鱼)과 같은 소수 요리 수안 탕 유) 널리 즐긴다.

- 저장성 (浙菜 제까이): 항저우, 닝보, 소흥의 음식을 포함합니다. 종종 수프에 제공되는 해산물과 야채의 섬세하게 조미된 가벼운 맛의 혼합. 때로는 살짝 달게, 때로는 새콤하게, 절강 요리는 고기와 야채를 함께 요리하는 경우가 많습니다.

- 하이난 (琼菜 치옹 카이): 중국인들 사이에서는 유명하지만, 해산물과 코코넛을 많이 사용하는 것이 특징인 외국인들에게는 아직 상대적으로 알려지지 않았습니다. 대표 특산품은 "하이난 4대 명물"(海南四大名菜) Hǎinán Sì Dà Míngcài): 문창 치킨(文昌鸡) 원창지), 동산염소(东山羊) 동산 양), 지아지오리(加积鸭) 지아지야) 및 헬레 게(和乐蟹) 헬레 시에). Wenchang 치킨은 결국 싱가포르와 말레이시아에서 하이난 치킨 라이스를 낳을 것입니다. 카오 맨 카이 (ข้าวมันไก่) Cơm gà Hải Nam 베트남에서.

- 중국 동북부 (东北 동베이) 고유의 음식 스타일이 있습니다. 쌀보다 밀을 강조하고 북서부와 마찬가지로 다양한 빵과 국수 요리와 케밥(串 추안; 캐릭터가 케밥처럼 보이는지 확인하십시오!). 이 지역은 특히 유명합니다 jiǎozi (饺子), 일본과 밀접한 관련이 있는 만두의 일종 교자 라비올리 또는 페로지와 유사합니다. 더 남쪽에 있는 많은 도시에는 교자 식당이 많고 그 중 많은 곳이 둥베이 사람들이 운영합니다.

의 요리 홍콩 과 마카오 각각 영국과 포르투갈의 영향을 받았지만 본질적으로 광동 요리입니다. 대만 와 비슷하다. 남복건성, 비록 일본의 영향을 받았지만 1949년에 본토를 탈출한 민족주의자들이 가져온 조리법의 결과로 중국의 다른 지역에서 영향을 받았습니다. 즉, 많은 유명 셰프들이 중국 본토를 떠나 홍콩과 대만으로 향했습니다. 공산주의 혁명의 영향으로 중국 전역의 고품질 요리도 해당 지역에서 사용할 수 있습니다.

성분

일곱 가지 필수품 오래된 중국 속담에 따르면 문을 열고(그리고 가정을 꾸리기 위해) 일곱 가지가 필요합니다. 장작, 쌀, 기름, 소금, 간장, 식초, 그리고 차. 물론 장작은 오늘날 거의 필수품이 아니지만 나머지 6개는 중국 요리의 핵심 요소에 대한 진정한 의미를 제공합니다. 칠리 페퍼와 설탕은 일부 지역 중국 요리의 중요성에도 불구하고 목록에 포함되지 않습니다. |

- 고기, 특히 돼지 고기는 어디에나 있습니다. 오리, 닭고기 등의 가금류도 인기가 많으며 소고기도 부족함이 없다. 양고기와 염소는 이슬람교도와 일반적으로 중국 서부에서 인기가 있습니다. 어디로 가야하는지 안다면 뱀이나 개와 같은 더 특이한 고기를 맛볼 수도 있습니다.

- 햄 — 유럽과 미국의 햄은 국제적으로 더 잘 알려져 있지만 중국은 전통적인 햄 생산 국가이기도 합니다. 일부 프리미엄 햄은 수세기 또는 수천 년 전으로 거슬러 올라가는 역사를 가지고 있습니다. 중국식 햄은 일반적으로 건조 경화되며 종종 수프 베이스로 사용되거나 다양한 요리의 재료로 사용됩니다. 중국에서 가장 유명한 햄은 진화(金華火) 시의 진화햄(金華火腿 jīn huá huǒ tuǐ)이다. 저장성 지방. 진화햄 외에 루가오 햄(如皋火腿 rú gāo huǒ tuǐ) 강소 지방, Xuanwei ham (宣威火腿 xuān wēi huǒ tuǐ) 윈난 중국의 "삼대 햄"을 모으는 성. 다른 유명한 햄으로는 안푸의 안푸햄(安福火腿 ān fú huǒ tuǐ)이 있습니다. 장시 1915년 파나마-태평양 만국박람회에 출품된 성, 윈난성 느오뎅의 느오뎅햄(诺邓火腿 nuò dèng huǒ tuǐ)은 바이족의 특산품이다.

- 쌀 특히 중국 남부의 전형적인 주식입니다.

- 국수 밀면(面, miàn)은 중국 북부에서, 쌀국수(粉, fěn)는 남부에서 더 많이 사용되는 중요한 주식입니다.

- 야채 일반적으로 찌거나, 절이거나, 볶거나 삶습니다. 생으로 먹는 경우는 드뭅니다. 많은 사람들이 여러 이름을 가지고 있고 다양한 방식으로 번역 및 오역되어 메뉴를 이해하려고 할 때 많은 혼란을 야기합니다. 좋아하는 음식으로는 가지, 완두콩 순, 연근, 무, 죽순이 있습니다. 조롱박에는 호리병박, 비터 멜론, 호박, 오이, 해면 조롱박 및 겨울 멜론이 포함됩니다. 잎이 많은 채소는 다양하지만 대부분은 영어 사용자에게 다소 생소하며 일종의 양배추, 상추, 시금치 또는 채소로 번역될 수 있습니다. 따라서 배추, 긴 잎 상추, 물 시금치, 고구마 채소 등을 찾을 수 있습니다.

- 버섯 – 고무 같은 검은 "나무 귀"에서 쫄깃한 흰색 "황금 바늘 버섯"에 이르기까지 다양한 종류.

- 두부 중국에서 채식은 단순히 채식주의자를 대체하는 것이 아니라 야채, 고기 또는 계란과 함께 제공되는 다른 종류의 음식입니다. 그것은 다양한 형태로 제공되며, 국제적으로 사용 가능한 직사각형 흰색 블록에 익숙하다면 대부분은 완전히 인식할 수 없을 것입니다.

특정 중국 요리에는 개, 고양이, 뱀 또는 멸종 위기에 처한 종과 같이 일부 사람들이 피하고 싶어하는 재료가 포함되어 있습니다. 그러나 그것은 매우 가능성이 낮은 실수로 이 요리를 주문하게 될 것입니다. 개와 뱀은 일반적으로 재료를 숨기지 않는 전문 레스토랑에서 제공됩니다. 분명히, 멸종 위기에 처한 재료로 만든 제품은 천문학적인 가격을 가질 것이고 어쨌든 정규 메뉴에 나열되지 않을 것입니다. 또한 도시의 선전 과 주하이 고양이와 개고기 섭취를 금지했으며, 이 금지령은 전국적으로 확대될 예정입니다.

또한 한의학에서는 개, 고양이, 뱀을 과도하게 먹으면 역효과가 있다고 하여 중국인들이 자주 먹지 않는다고 합니다.

대체로 쌀이 남쪽의 주요 주식이고 밀이 주로 국수 형태인 반면 북쪽의 주요 주식입니다. 이러한 필수품은 항상 존재하며 중국에서 쌀, 국수 또는 둘 다를 먹지 않고 하루를 보내지 않는다는 것을 알게 될 것입니다.

빵 유럽 국가들에 비해 유비쿼터스가 거의 없지만 중국 북부에는 좋은 납작빵이 많고, 바오지 (包子) (광둥어: 바오) - 달콤하거나 짭짤한 속을 채운 찐 만두는 광둥어 딤섬과 다른 나라에서도 인기가 있습니다. 속을 채우지 않은 빵은 다음과 같이 알려져 있습니다. 만투 (馒头/饅頭)은 중국 북부에서 인기 있는 아침 식사 요리입니다. 이들은 찐 또는 튀김으로 제공될 수 있습니다. 티베트와 위구르 요리는 북부 지방의 것과 유사한 플랫브레드를 많이 사용합니다. 인도 그리고 중동.

다음과 같은 소수 민족 지역을 제외하고 윈난, 티베트, 몽골 내륙 지방 과 신장, 낙농 제품은 전통적인 중국 요리에서 일반적이지 않습니다. 세계화로 인해 유제품이 다른 국가의 일부 식품에 통합되고 있으므로 예를 들어 바오지에 커스터드를 채운 것을 볼 수 있지만 이는 예외입니다. 유제품은 또한 강한 서구의 영향으로 인해 중국 본토의 음식보다 홍콩, 마카오 및 대만의 요리에서 다소 더 일반적으로 사용됩니다.

유제품이 흔하지 않은 한 가지 이유는 대다수의 중국 성인이 유당 불내증입니다. 유당(유당)을 소화하는 데 필요한 효소가 없기 때문에 대신 장내 세균에 의해 소화되어 가스를 생성합니다. 따라서 많은 양의 유제품은 상당한 고통과 당혹감을 유발할 수 있습니다. 이 상태는 북유럽인의 10% 미만에서 발생하지만 아프리카 일부 지역에서는 인구의 90% 이상에서 발생합니다. 중국은 그 사이 어딘가에 있으며, 요금에는 지역적, 민족적 차이가 있습니다. 요구르트는 중국에서 아주 일반적입니다. 박테리아가 이미 유당을 분해했기 때문에 문제가 발생하지 않습니다. 일반적으로 요구르트는 우유보다 찾기 쉽고 치즈는 고가의 사치품입니다.

그릇

중국에서는 모든 종류의 고기, 야채, 두부 및 국수 요리를 찾을 수 있습니다. 다음은 잘 알려진 몇 가지 독특한 요리입니다.

- 부처가 벽을 뛰어 넘다 (佛跳墙, 포티아오창) – 비싸다 푸저우어 상어 지느러미로 만든 수프(鱼翅, 유치), 전복 및 기타 많은 비채식주의 프리미엄 재료. 전설에 따르면 그 향이 너무 좋아서 한 승려가 채식 서약을 잊고 사찰 담을 뛰어넘어 음식을 먹었다고 합니다. 일반적으로 준비 시간이 길기 때문에 며칠 전에 주문해야 합니다.

- 구오바오루우 锅包肉(돼지고기 탕수육) 중국 동북부.

- 닭 발 (鸡爪, 지주) – 중국의 많은 사람들은 닭고기를 가장 맛있는 부위로 생각합니다. 봉황의 발톱(凤爪) 풍자우 광둥어로, 풍주 만다린) 광둥어 사용 지역에서 인기있는 딤섬 요리이며 가장 일반적으로 검은 콩 소스로 만들어집니다.

- 마파두부 (麻婆豆腐, 마포 두푸) - ㅏ 사천어 아주 매운 두부 돼지고기 요리 말라 얼얼하다/마비되는 매운맛.

- 북경 오리 (北京烤鸭, 베이징 카오야) – 오리 구이, 가장 유명한 요리 특징 베이징.

- 냄새나는 두부 (臭豆腐, 주두푸) – 소리가 나는 대로. 여러 지역에 다른 유형이 있지만 가장 유명한 것은 창사-스타일, 외부가 검게 칠해진 직사각형 블록으로 만들어집니다. 접시의 다른 눈에 띄는 스타일은 다음과 같습니다 소흥-스타일과 난징-스타일. 한국에서도 아주 유명한 길거리 음식입니다 대만, 다양한 스타일로 제공됩니다.

- 속을 채운 두부 (酿豆腐, 니앙 두푸 북경어로, 옹옹4 테우4 부4 Hakka) – Hakka 요리, 고기로 속을 채운 튀긴 두부, 용 타우 푸 동남아시아에서는 종종 원본에서 크게 수정되었습니다.

- 샤오롱바오 小笼包(小笼包) - 작은 수프를 넣은 만두 상하이, 강소 과 저장성.

- 탕수육 (咕噜肉 굴루루 북경어로, 구루유크 in Cantonese) – 19세기 동안 광동에 기반을 둔 유럽인과 미국인의 입맛에 맞게 발명된 광둥 요리. 영어권 국가에서 가장 인기 있는 중국 요리 중 하나입니다.

- 뜨겁고 신 수프 (酸辣汤 수안라탕) – 고추로 맵고 식초로 신맛이 나는 걸쭉하고 녹말이 많은 수프. 쓰촨 요리의 명물.

- 굴 오믈렛 (海蛎煎 hǎilì jiān 또는 蚝煎 하오 지안) — 계란, 신선한 굴, 고구마 전분으로 만든 요리 남복건성 과 차오산, 다양한 변형이 있지만. 아마도 국제적으로 가장 유명한 변형은 섬의 야시장에서 흔히 볼 수 있는 대만 버전일 것입니다. 싱가포르, 페낭 및 방콕과 같이 앞서 언급한 지역의 대규모 디아스포라 커뮤니티가 있는 지역에서도 다른 변형을 찾을 수 있습니다.蚵仔煎라고 한다.오아치안) 민난어 사용 지역(중국어 이름이 거의 알려지지 않은 대만 포함) 및 蠔烙(영형5 루아4) 테오츄어를 사용하는 지역에서.

국수

국수는 중국에서 유래: 국수에 대한 가장 오래된 기록은 약 2,000년 전으로 거슬러 올라가며 고고학적 증거는 4,000년 전에 동부 라지아에서 국수를 소비했다는 보고가 있습니다. 칭하이. 중국어에는 국수에 대한 단일 단어가 없으며 대신 미안 (面) 밀로 만든, 펜 (粉) 쌀이나 때로 다른 녹말로 만든 것. 국수는 재료, 폭, 준비 방법 및 토핑이 다양한 지역에 따라 다르지만 일반적으로 일종의 고기 및/또는 야채와 함께 제공됩니다. 그들은 수프와 함께 제공되거나 건조(소스만 포함)와 함께 제공될 수 있습니다.

국수에 사용되는 소스와 향료에는 사천식 짠맛(麻辣, málà) 소스, 참깨 소스(麻酱, májiàng), 간장(酱油 jiàngyóu), 식초(醋, cù) 등이 있습니다.

- 비앙비앙 국수 (

.svg/15px-Biang_(简体).svg.png)

.svg/15px-Biang_(简体).svg.png) 面, biángbiáng miàn) - 두껍고 폭이 넓고 쫄깃한 수제 국수 산시, 이름이 너무 복잡하고 거의 사용되지 않은 문자로 작성되어 사전에 나열되지 않고 대부분의 컴퓨터에서 입력할 수 없습니다(더 큰 버전을 보려면 문자를 클릭하십시오). 또한 문자를 올바르게 인쇄할 수 없는 메뉴에서 油泼面 yóupō miàn으로 나열되는 것을 볼 수도 있습니다.

面, biángbiáng miàn) - 두껍고 폭이 넓고 쫄깃한 수제 국수 산시, 이름이 너무 복잡하고 거의 사용되지 않은 문자로 작성되어 사전에 나열되지 않고 대부분의 컴퓨터에서 입력할 수 없습니다(더 큰 버전을 보려면 문자를 클릭하십시오). 또한 문자를 올바르게 인쇄할 수 없는 메뉴에서 油泼面 yóupō miàn으로 나열되는 것을 볼 수도 있습니다. - 충칭 국수 (重庆小面, Chóngqìng xiǎo miàn) – 일반적으로 수프와 함께 제공되는 얼얼하고 매운 국수, 아마도 가장 유명한 요리일 것입니다. 충칭 뜨거운 냄비와 함께.

- 단단미안 (担担面) - 사천어 얼얼하고 매운 얇은 국수, "건조" 또는 수프와 함께 제공됩니다.

- 볶음면 (炒面, chǎo miàn 및 炒粉 chǎo fěn 또는 河粉 héfěn) – 다른 국가의 중국 레스토랑 방문객에게 "차우멘"와 "차우 재미" 광둥어 발음에 따라 이 볶음 국수는 지역에 따라 다릅니다. 해외 중국 식당에서 흔히 볼 수 있는 것처럼 항상 기름지고 무겁지는 않습니다. chǎo fàn(炒饭)과 혼동하지 마십시오. 볶음밥.

- 뜨거운 마른 국수 (热干面, règānmiàn) 소스를 곁들인 면 요리로, 수프 없이 제공된다는 의미에서 "건조"합니다. 의 전문 우한, 후베이.

- 칼국수 (刀削面, dāoxiāo miàn) – ~에서 산시, 얇지는 않지만 정확히 넓지도 않은, 다양한 소스와 함께 제공됩니다. "씹을수록 맛있습니다."

- 란저우 라미안 (兰州拉面, Lánzhōu lāmiàn) 신선한 란저우- 스타일의 손으로 뽑은 국수. 이 산업은 회족(回族) 종족이 크게 지배하고 있습니다. 이슬람 복장을 한 직원, 남자는 흰색 페즈 모자, 여자는 스카프를 두르는 작은 식당을 찾으세요. 찾고 있다면 할랄 무슬림이 다수인 지역 밖의 음식을 먹을 수 있는 이 레스토랑은 좋은 선택이 될 것입니다. 많은 레스토랑에 중국어나 아랍어로 "할랄"(清真, qīngzhēn)이라고 광고하는 표지판이 있습니다.

- 량피 (凉皮) 납작하게 차게 차게 내어주는 면. 산시.

- 로 마인 (拌面, bàn miàn) - 소스를 곁들인 얇고 마른 국수.

- 장수 국수 (长寿面, chángshòu miàn)은 장수를 상징하는 긴 국수인 전통적인 생일 요리입니다.

- 루오시펜 螺蛳粉(螺蛳粉) - 강 달팽이 국물을 곁들인 국수 광시.

- 다리 위 국수 (过桥米线, guò qiáo mǐxiàn) - 쌀국수 윈난.

- 완탕면 (云吞面 yún tūn miàn) – 새우 만두와 함께 수프에 제공되는 얇은 계란 국수로 구성된 광둥 요리. 디아스포라 광둥인들 사이에 다양한 요리가 존재합니다. 동남아시아, 비록 종종 원본에서 크게 수정되었지만.

간식

다양한 종류의 중국 음식은 빠르고 저렴하고 맛있고 가벼운 식사를 제공합니다. 이동식 노점상과 별장에서 판매하는 길거리 음식과 스낵은 중국 도시 전역에서 찾을 수 있으며 특히 아침이나 간식으로 좋습니다. 왕푸징 지구 스낵 스트리트 베이징에서 관광객이라면 주목할만한 거리 음식 지역입니다. 광둥어를 사용하는 지역에서는 길거리 음식 노점상을 가이빈동; 이러한 벤처는 전통적인 길거리 음식 의미에서 겨우 "이동 가능한" 포장마차와 함께 실질적인 비즈니스로 성장할 수 있습니다. 작은 노점상 외에도 이러한 품목 중 일부는 레스토랑의 메뉴나 세븐일레븐과 같은 편의점의 카운터에서 찾을 수 있습니다. 전국적으로 제공되는 다양한 간편식에는 다음이 포함됩니다.

- 바오지 包子(包子) – 야채, 고기, 팥소, 커스터드 또는 검은 깨와 같은 달콤하거나 짭짤한 속을 채워 찐 만두

- 고기바베큐(串) 추안) 노점상. 캐릭터도 케밥처럼 생겨서 찾기 쉬움! 신강식 양고기 케밥(羊肉串) 양그루 추안) 특히 유명하다.

- 죽 (粥) 주 또는 稀饭 시판) - 쌀죽. 그만큼 광둥어, 터츄 과 민난 특히 사람들은 이 겉보기에 단순한 요리를 예술 형식으로 승격시켰습니다. 그들 각각은 고유의 독특하고 유명한 스타일을 가지고 있습니다.

- 피쉬볼 (鱼丸 유완) - 공 모양으로 성형된 어묵, 많은 해안 지역에서 인기 광동 과 복건, 뿐만 아니라 홍콩 과 대만. 특히 두 도시는 이 요리의 버전으로 전 세계 화교들 사이에서 유명합니다. 산터우-스타일의 생선 공은 일반적으로 속이 없는 평범한 반면, 푸저우-스타일 피쉬볼은 일반적으로 다진 돼지고기로 채워져 있습니다.

- 지안뱅 煎饼(煎饼): 크래커에 소스와 칠리 소스를 곁들인 계란 팬케이크.

- Jiǎozi 중국어로 "만두"로 번역되는 饺子(饺子)는 중국 북부의 많은 지역에서 주식으로 다양한 속을 넣은 삶거나 찜 또는 튀긴 라비올리 같은 품목입니다. 이것들은 아시아 전역에서 발견됩니다. momos, mandu, gyoza 및 jiaozi는 모두 기본적으로 동일한 것의 변형입니다.

- 만터우 馒头(馒头) - 찐 만두로, 연유와 함께 자주 먹습니다.

- 두부 푸딩 (豆花, 두후아; 또는 豆腐花, 두푸후아) – 중국 남부에서 이 부드러운 푸딩은 일반적으로 달콤하며 팥이나 시럽과 같은 토핑과 함께 제공될 수 있습니다. 중국 북부에서는 간장으로 만든 짭짤한 맛이 나는 음식으로 종종 dòufunǎo (豆腐脑), 문자 그대로 "두부 뇌". 대만에서는 달고 수분이 많아 음식처럼 술처럼 마신다.

- 워워투 窝窝头(窝窝头) – 중국 북부에서 인기 있는 원뿔 모양의 찐 옥수수 빵

- 유티아오 (油条) – 문자 그대로 "기름 띠", 광둥어 사용 지역에서 "튀긴 유령"(油炸鬼)으로 알려진 길고 푹신한 기름진 페이스트리의 일종. 두유를 곁들인 Youtiao는 전형적인 대만 아침 식사이며, youtiao는 광둥 요리에서 죽의 일반적인 조미료입니다. 전설에 따르면 유티아오는 남송 시대에 애국적인 장군을 누명을 씌운 공모자에 대한 평민의 항의였다고 합니다.

- 자가오 炸糕(炸糕) - 약간 달달하게 튀긴 과자

- Zòngzi (粽子) – 대나무 잎으로 싸인 큰 찹쌀 만두로, 전통적으로 5월이나 6월 단오절(단오절)에 먹습니다. 드래곤 보트 축제에는 다른 종류의 만두와 만두를 판매하는 상점에서 판매하는 것을 볼 수 있으며 다른 계절에도 볼 수 있습니다. 속재료는 짭짤할 수 있다(咸的 시안 데) 고기나 계란, 또는 달콤한(甜的) 티안 데). 짭짤한 것은 중국 남부에서 더 인기가 있고 북부에서는 달콤합니다.

또한 유비쿼터스 베이커리(面包店, miànbāodiàn)에서 일반적으로 달콤한 다양한 품목을 찾을 수 있습니다. 중국에서 볼 수 있는 다양한 과자와 단 음식은 서구처럼 식당에서 식후 디저트 코스로 판매되기보다는 간식으로 판매되는 경우가 많습니다.

과일

- 용과 (火龙果, huǒlóngguǒ) 낯익은 과일은 분홍색 피부, 분홍색 또는 녹색의 부드러운 이삭이 튀어나오며, 흰색 또는 빨간색 과육과 검은색 씨가 있는 이상한 과일입니다. 과육이 붉은 것이 더 달고 비싸지만 흰색이 더 시원하다.

- 대추 (枣, zǎo), 크기와 모양 때문에 "중국 대추"라고도 하지만 맛과 질감은 사과에 가깝습니다. 여러 종류가 있으며 신선하거나 말린 것을 구입할 수 있습니다. 다양한 광둥 수프를 만드는 데 자주 사용됩니다.

- 키위 과일 (猕猴桃, míhóutáo, 또는 때때로 奇异果, qíyìguǒ) 중국이 원산지로, 짙은 녹색에서 주황색까지 다양한 과육을 가진 크고 작은 다양한 품종을 찾을 수 있습니다. 많은 사람들이 진정으로 익은 키위를 맛본 적이 없습니다. 칼로 잘라야 하는 타르트 키위에 익숙하다면 스스로에게 호의를 베풀고 신선하고 잘 익은 제철 키위를 맛보십시오.

- 용안 (龙眼, lóngyǎn, 문자 그대로 "용의 눈")은 더 잘 알려진 리치(아래)와 비슷하지만 더 작으며 약간 더 가벼운 맛과 더 부드럽고 연한 노란색 또는 갈색 껍질이 있습니다. 그것은 리치보다 약간 늦게 중국 남부에서 수확되지만, 다른 시기에도 판매를 위해 찾을 수 있습니다.

- 그 열매 (荔枝, lìzhī)는 놀랍도록 달콤하고 육즙이 많은 과일로 약간 향긋한 맛이 나며 껍질이 붉을 때 가장 좋습니다. 중국 남부지방에서 늦봄과 초여름에 수확한다. 광동 지방.

- 망고 스틴 (山竹, shānzhú) 작은 사과 크기의 짙은 자주색 열매. 먹으려면 두꺼운 껍질이 갈라질 때까지 밑에서 꾹꾹 눌러준 후 개봉하여 달달한 하얀 과육을 먹습니다.

- 자두 (梅子, méizi; 李子, lǐzi) – 중국 매실은 일반적으로 북미에서 볼 수 있는 매실보다 작고 단단하며 시큼합니다. 그들은 신선하거나 말린 것이 인기가 있습니다.

- 양메이 杨梅(杨梅)는 자두의 일종으로 표면이 곱고 옹이가 있다. 달콤하고 낟알 같은 딸기나 라즈베리처럼 설명하기 어려운 질감이 있습니다.

- 포멜로 (柚子, yòuzi) – 때때로 "중국 자몽"이라고도 하지만 실제로 자몽은 이 큰 감귤류와 오렌지 사이의 교배종입니다. 과육은 자몽보다 달지만 육즙이 적어 손으로 먹을 수 있고 칼이나 숟가락이 필요하지 않습니다. 가을에 수확한 포멜로는 너무 커서 한 사람이 먹기에 너무 크므로 동료들과 나눠 먹습니다.

- 왐피 (黄皮, huángpí), 용안 및 리치와 비슷하지만 포도 모양이고 약간 신맛이 나는 또 다른 과일입니다.

- 수박 (西瓜, xīguā)는 여름에 매우 일반적으로 사용됩니다. 중국 수박은 1차원적으로 길쭉한 것이 아니라 구형인 경향이 있습니다.

중국에서는 토마토와 아보카도를 과일로 간주합니다. 아보카도는 흔하지 않지만 토마토는 종종 간식으로 먹거나 디저트의 재료로 먹거나 스크램블 에그와 함께 볶습니다.

음료수

차

.jpg/220px-China_-_Chengdu_4_-_green_tea_in_the_park_(135953545).jpg)

차 (茶, cha)는 물론 식당과 전용 찻집에서 찾을 수 있습니다. 우유나 설탕을 넣지 않은 보다 전통적인 "깔끔한" 차에 더하여, 버블티 우유와 타피오카 볼 (뜨거운 또는 차가운 제공)이 인기가 있으며 상점과 자판기에서 병에 담긴 달콤한 아이스티를 찾을 수 있습니다.

중국은 차 문화의 발상지이며, 뻔한 이야기를 할 위험이 있습니다. 차 (다 차) 중국에서. 녹차(绿茶) 라차)는 일부 레스토랑(지역에 따라 다름)에서 무료로 제공되거나 소정의 비용으로 제공됩니다. 제공되는 몇 가지 일반적인 유형은 다음과 같습니다.

- 화약차 (珠茶 주차): 녹차라는 이름은 맛이 아니라 차를 끓이는 데 사용되는 잎이 뭉쳐진 모양에서 따온 것입니다(중국 이름 "진주차"는 다소 시적입니다).

- 자스민 차 (茉莉花茶 모리와차): 자스민 꽃 향이 나는 녹차

- 우롱 (烏龍 우롱): a half-fermented mountain tea.

However, specialist tea houses serve a vast variety of brews, ranging from the pale, delicate white tea (白茶 báichá) to the powerful fermented and aged pu'er tea (普洱茶 pǔ'ěrchá).

The price of tea in China is about the same as anywhere else, as it turns out. Like wine and other indulgences, a product that is any of well-known, high-quality or rare can be rather costly and one that is two or three of those can be amazingly expensive. As with wines, the cheapest stuff should usually be avoided and the high-priced products left to buyers who either are experts themselves or have expert advice, but there are many good choices in the middle price ranges.

Tea shops typically sell by the jin (斤 jīn, 500g, a little over an imperial pound); prices start around ¥50 a jin and there are many quite nice teas in the ¥100-300 range. Most shops will also have more expensive teas; prices up to ¥2,000 a jin are fairly common. The record price for top grade tea sold at auction was ¥9,000 per gram; that was for a rare da hong pao from Mount Wuyi from a few bushes on a cliff, difficult to harvest and once reserved for the Emperor.

Various areas of China have famous teas, but the same type of tea will come in many different grades, much as there are many different burgundies at different costs. Hangzhou, near Shanghai, is famed for its "Dragon Well" (龙井 lóngjǐng) green tea. 복건 과 Taiwan have the most famous oolong teas (乌龙茶 wūlóngchá), "Dark Red Robe" (大红袍 dàhóngpáo) from Mount Wuyi, "Iron Goddess of Mercy" (铁观音 tiěguānyīn) from Anxi, and "High Mountain Oolong" (高山烏龍 gāoshān wūlóng) from Taiwan. Pu'er in Yunnan has the most famous fully fermented tea, pǔ'ěrchá (普洱茶). This comes compressed into hard cakes, originally a packing method for transport by horse caravan to Burma and Tibet. The cakes are embossed with patterns; some people hang them up as wall decorations.

Most tea shops will be more than happy to let you sit down and try different varieties of tea. Tenfu Tea [1] is a national chain and in Beijing "Wu Yu Tai" is the one some locals say they favor.

Black tea, the type of tea most common in the West, is known in China as "red tea" (紅茶 hóngchá). While almost all Western teas are black teas, the converse isn't true, with many Chinese teas, including the famed Pǔ'ěr also falling into the "black tea" category.

Normal Chinese teas are always drunk neat, with the use of sugar or milk unknown. However, in some areas you will find Hong Kong style "milk tea" (奶茶 nǎichá) or Tibetan "butter tea". Taiwanese bubble tea (珍珠奶茶 Zhēnzhū Nǎichá) is also popular; the "bubbles" are balls of tapioca and milk or fruit are often mixed in.

커피

커피 (咖啡 kāfēi) is becoming quite popular in urban China, though it can be quite difficult to find in smaller towns.

Several chains of coffee shops have branches in many cities, including Starbucks (星巴克), UBC Coffee (上岛咖啡), Ming Tien Coffee Language and SPR, which most Westerners consider the best of the bunch. All offer coffee, tea, and both Chinese and Western food, generally with good air conditioning, wireless Internet, and nice décor. In most locations they are priced at ¥15-40 or so a cup, but beware of airport locations which sometimes charge around ¥70.

There are many small independent coffee shops or local chains. These may also be high priced, but often they are somewhat cheaper than the big chains. Quality varies from excellent to abysmal.

For cheap coffee just to stave off withdrawal symptoms, there are several options. Go to a Western fast food chain (KFC, McD, etc.) for some ¥8 coffee. Alternately, almost any supermarket or convenience store will have both canned cold coffee and packets of instant Nescafé (usually pre-mixed with whitener and sugar) - just add hot water. It is common for travellers to carry a few packets to use in places like hotel rooms or on trains, where coffee may not be available but hot water almost always is.

Other non-alcoholic drinks

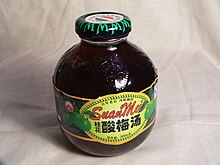

- Sour prune juice (酸梅汤 suānméitāng) – sweet and sour, and quite a bit tastier than what you might know as "prune juice" back home. Served at restaurants fairly often.

- Soymilk (豆浆 dòujiāng) – different from the stuff that's known as "soymilk" in Europe or the Americas. You can find it at some street food stalls and restaurants. The server may ask if you want it hot (热 rè) or cold (冷 lěng); otherwise the default is hot. Vegans and lactose-intolerant people beware: there are two different beverages in China that are translated as "soymilk": 豆浆 dòujiāng should be dairy-free, but 豆奶 dòunǎi may contain milk.

- Apple vinegar drink (苹果醋饮料 píngguǒ cù yǐnliào) – it might sound gross, but don't knock it till you try it! A sweetened carbonated drink made from vinegar; look for the brand 天地壹号 Tiāndì Yīhào.

- Herbal tea (凉茶 liáng chá) – a specialty of Guangdong. You can find sweet herbal tea drinks at supermarkets and convenience stores – look for the popular brands 王老吉 Wánglǎojí and 加多宝 Jiāduōbǎo. Or you can get the traditional, very bitter stuff at little shops where people buy it as a cold remedy.

- Winter melon punch (冬瓜茶 dōngguā chá) – a very sweet drink that originated in Taiwan, but has also spread to much of southern China and the overseas Chinese communities in Southeast Asia.

- Hot water (热水 rè shuǐ) – traditionally in China, ordinary water is drunk hot rather than cold. It may seem counterintuitive, but drinking hot water helps you sweat and thus cool off during the hot summer months. Nowadays there are plenty of people in China who drink cold water too, but if you happen to get a cold or feel ill during your trip, you're sure to hear lots of people advising you: "Drink more hot water."

Alcoholic

- 또한보십시오: China#Drink

- Báijiǔ (白酒) is very strong, clear grain liquor, made from sorghum and sometimes other grains depending on the region. The word "jiǔ" can be used for any alcoholic drink, but is often translated as "wine". Chinese may therefore call baijiu "white wine" in conversation, but "white lightning" would be a better translation, since it is generally 40% to 65% alcohol by volume.

- Baijiu will typically be served at banquets and festivals in tiny shot glasses. Toasts are ubiquitous at banquets or dinners on special occasions. Many Chinese consume baijiu only for this ceremonial purpose, though some — more in northern China than in the south — do drink it more often.

- Baijiu is definitely an acquired taste, but once the taste is acquired, it's quite fun to "ganbei" (toast) a glass or two at a banquet.

- Maotai (茅台 Máotái) or Moutai, made in 구이저우 Province, is China's most famous brand of baijiu and China's national liquor. Made from sorghum, Maotai and its expensive cousins are well known for their strong fragrance and are actually sweeter than western clear liquors as the sorghum taste is preserved — in a way.

- Wuliangye (五粮液 Wǔliángyè) from Yibin, 쓰촨 is another premium type of baijiu. Its name literally translates as "five grains liquor", referring to the five different types of grains that go into its production, namely sorghum, glutinous rice, rice, wheat and maize. Some of its more premium grades are among the most expensive liquors in the world, retailing at several thousand US dollars per bottle.

- Kaoliang (高粱酒 gāoliángjiǔ) is a premium type of sorghum liquor most famously made on the island of Kinmen under the eponymous brand Kinmen Kaoling Liquor, which while just off the coast of Xiamen is controlled by Taiwan. Considered to be the national drink of Taiwan.

- The cheapest baijiu is the Beijing-brewed èrguōtóu (二锅头). It is most often seen in pocket-size 100 ml bottles which sell for around ¥5. It comes in two variants: 53% and 56% alcohol by volume. Ordering "xiǎo èr" (erguotou's diminutive nickname) will likely raise a few eyebrows and get a chuckle from working-class Chinese.

- There are many brands of baijiu, and as is the case with other types of liquor, both quality and price vary widely. Foreigners generally try only low-end or mid-range baijiu, and they are usually unimpressed; the taste is often compared to diesel fuel. However a liquor connoisseur may find high quality, expensive baijiu quite good.

.jpg/220px-Tsingtao_(28439950155).jpg)

- Beer (啤酒 píjiǔ) is common in China, especially the north. Beer is served in nearly every restaurant and sold in many grocery stores. The typical price is about ¥2.5-4 in a grocery store, ¥4-18 in a restaurant, around ¥10 in an ordinary bar, and ¥20-40 in a fancier bar. Most places outside of major cities serve beer at room temperature, regardless of season, though places that cater to tourists or expatriates have it cold. The most famous brand is Tsingtao (青島 Qīngdǎo) from Qingdao, which was at one point a German concession. Other brands abound and are generally light beers in a pilsner or lager style with 3-4% alcohol. This is comparable to many American beers, but weaker than the 5-6% beers found almost everywhere else. In addition to national brands, most cities will have one or more cheap local beers. Some companies (Tsingtao, Yanjing) also make a dark beer (黑啤酒 hēipíjiǔ). In some regions, beers from other parts of Asia are fairly common and tend to be popular with travellers — Filipino San Miguel in Guangdong, Singaporean 호랑이 in Hainan, and Laotian Beer Lao in Yunnan.

- Grape wine: Locally made grape wine (葡萄酒 pútáojiǔ) is common and much of it is reasonably priced, from ¥15 in a grocery store, about ¥100-150 in a fancy bar. However, most of the stuff bears only the faintest resemblance to Western wines. The Chinese like their wines red and very sweet, and they're typically served over ice or mixed with Sprite.

- Great Wall 과 Dynasty are large brands with a number of wines at various prices; their cheaper (under ¥40) offerings generally do not impress Western wine drinkers, though some of their more expensive products are often found acceptable.

- China's most prominent wine-growing region is the area around Yantai. Changyu is perhaps its best-regarded brand: its founder introduced viticulture and winemaking to China in 1892. Some of their low end wines are a bit better than the competition.

- In addition to the aforementioned Changyu, if you're looking for a Chinese-made, Western-style wine, try to find these labels:

- Suntime[데드 링크], with a passable Cabernet Sauvignon

- Yizhu, in Yili and specializing in ice wine

- Les Champs D'or, French-owned and probably the best overall winery in China, from Xinjiang

- Imperial Horse and Xixia, from Ningxia

- Mogao Ice Wine, Gansu

- Castle Estates, Shandong

- Shangrila Estates, from Zhongdian, Yunnan

- Wines imported from Western countries can also be found, but they are often extremely expensive. For some wines, the price in China is more than three times what you would pay elsewhere.

- There are also several brands and types of rice wine. Most of these resemble a watery rice pudding, they are usually sweet and contain a minute amount of alcohol for taste. Travellers' reactions to them vary widely. These do not much resemble Japanese sake, the only rice wine well known in the West.

- 중국말 brandy (白兰地 báilándì) is excellent value; like grape wine or baijiu, prices start under ¥20 for 750 ml, but many Westerners find the brandies far more palatable. A ¥18-30 local brandy is not an over ¥200 imported brand-name cognac, but it is close enough that you should only buy the cognac if money doesn't matter. Expats debate the relative merits of brandies including Chinese brand Changyu. All are drinkable.

- The Chinese are also great fans of various supposedly medicinal liquors, which usually contain exotic herbs and/or animal parts. Some of these have prices in the normal range and include ingredients like ginseng. These can be palatable enough, if tending toward sweetness. Others, with unusual ingredients (snakes, turtles, bees, etc.) and steep price tags, are probably best left to those that enjoy them.

Restaurants

Many restaurants in China charge a cover charge of a few yuan per person.

If you don't know where to eat, a formula for success is to wander aimlessly outside of the touristy areas (it's safe), find a place full of locals, skip empty places and if you have no command of Mandarin or the local dialect, find a place with pictures of food on the wall or the menu that you can muddle your way through. Whilst you may be persuaded to order the more expensive items on the menu, ultimately what you want to order is your choice, and regardless of what you order, it is likely to be far more authentic and cheaper than the fare that is served at the tourist hot spots.

Ratings

Yelp is virtually unknown in China, while the Michelin Guide only covers Shanghai and Guangzhou, and is not taken very seriously by most Chinese people. Instead, most Chinese people rely on local website Dazhong Dianping for restaurant reviews and ratings. While it is a somewhat reliable way to search for good restaurants in your area, the downside is that it is only in Chinese. In Hong Kong, some people use Open Rice for restaurant reviews and ratings in Chinese and English.

Types of restaurants

Hot pot restaurants are popular in China. The way they work varies a bit, but in general you choose, buffet-style, from a selection of vegetables, meat, tofu, noodles, etc., and they cook what you chose into a soup or stew. At some you cook it yourself, fondue-style. These restaurants can be a good option for travellers who don't speak Chinese, though the phrases là (辣, "spicy"), bú là (不辣, "not spicy") and wēilà (微辣, "mildly spicy") may come in handy. You can identify many hot pot places from the racks of vegetables and meat waiting next to a stack of large bowls and tongs used to select them.

Cantonese cuisine is known internationally for dim sum (点心, diǎnxīn), a style of meal served at breakfast or lunch where a bunch of small dishes are served in baskets or plates. At a dim sum restaurant, the servers may bring out the dishes and show them around so you can select whatever looks good to you or you may instead be given a checkable list of dishes and a pen or pencil for checking the ones you want to order. As a general rule, Cantonese diners always order shrimp dumplings (虾饺, xiājiǎo in Mandarin, hāgáau in Cantonese) and pork dumplings (烧卖, shāomài in Mandarin, sīumáai in Cantonese) whenever they eat dim sum, even though they may vary the other dishes. This is because the two aforementioned dishes are considered to be so simple to make that all restaurants should be able to make them, and any restaurant that cannot make them well will probably not make the other more complex dishes well. Moreover, because they require minimal seasoning, it is believed that eating these two dishes will allow you to gauge the freshness of the restaurant's seafood and meat.

Big cities and places with big Buddhist temples often have Buddhist restaurants serving unique and delicious all-vegetarian food, certainly worth trying even if you love meat. Many of these are all-you-can-eat buffets, where you pay to get a tray, plate, bowl, spoon, cup, and chopsticks, which you can refill as many times as you want. (At others, especially in Taiwan, you pay by weight.) When you're finished you're expected to bus the table yourself. The cheapest of these vegetarian buffets have ordinary vegetable, tofu, and starch dishes for less than ¥20 per person; more expensive places may have elaborate mock meats and unique local herbs and vegetables. Look for the character 素 sù or 齋/斋 zhāi, the 卍 symbol, or restaurants attached to temples.

Chains

Western-style fast food has become popular. KFC (肯德基), McDonald's (麦当劳), Subway (赛百味) and Pizza Hut (必胜客) are ubiquitous, at least in mid-sized cities and above. Some of them have had to change or adapt their concepts for the Chinese market; Pizza Hut is a full-service sit down restaurant chain in China. There are a few Burger Kings (汉堡王), Domino's and Papa John's (棒约翰) as well but only in major cities. (The menu is of course adjusted to suit Chinese tastes – try taro pies at McDonald's or durian pizza at Pizza Hut.) Chinese chains are also widespread. These include Dicos (德克士)—chicken burgers, fries etc., cheaper than KFC and some say better—and Kung Fu (真功夫)—which has a more Chinese menu.

- Chuanqi Maocai (传奇冒菜 Chuánqí Màocài). Chengdu-style hot pot stew. Choose vegetables and meat and pay by weight. Inexpensive with plenty of Sichuan tingly-spicy flavor.

- Din Tai Fung (鼎泰丰 Dǐng Tài Fēng). Taiwanese chain specializing in Huaiyang cuisine, with multiple locations throughout mainland China, Taiwan and Hong Kong, as well as numerous overseas locations throughout East and Southeast Asia, and in far-flung places such as the United State, United Kingdom and Australia. Particularly known for their soup dumplings (小笼包) and egg fried rice (蛋炒饭). The original location on Xinyi Road in 타이베이 is a major tourist attraction; expect to queue for 2 hours or more during peak meal times.

- 녹차 (绿茶 Lǜ Chá). Hangzhou cuisine with mood lighting in an atmosphere that evokes ancient China. Perhaps you'll step over a curved stone bridge as you enter the restaurant, sit at a table perched in what looks like a small boat, or hear traditional music drift over from a guzheng player while you eat.

- Haidilao Hot Pot (海底捞 Hǎidǐlāo). Expensive hot pot chain famous for its exceptionally attentive and courteous service. Servers bow when you come in and go the extra mile to make sure you enjoy your meal.

- Little Sheep (小肥羊). A mid-range hot pot chain that has expanded beyond China to numerous overseas locations such as the United States, Canada and Australia. Based on Mongol cuisine—the chain is headquartered in Inner Mongolia. The specialty is mutton but there are other meats and vegetable ingredients for the hot pot on the menu as well. One type of hot pot is called Yuan Yang (鸳鸯锅 yuān yāng guō). The hot pot is separated into two halves, one half contains normal non-spicy soup stock and the other half contains má là (numbing spicy) soup stock.

- Yi Dian Dian (1㸃㸃 / 一点点 Yìdiǎndiǎn). Taiwanese milk tea chain that now has lots of branches in mainland China.

Ordering

Chinese restaurants often offer an overwhelming variety of dishes. Fortunately, most restaurants have picture menus with photos of each dish, so you are saved from despair facing a sea of characters. Starting from mid-range restaurants, there is also likely to be a more or less helpful English menu. Even with the pictures, the sheer amount of dishes can be overwhelming and their nature difficult to make out, so it is often useful to ask the waiter to recommend (推荐 tuījiàn) something. They will often do so on their own if they find you searching for a few minutes. The waiter will usually keep standing next to your table while you peruse the menu, so do not be unnerved by that.

The two-menu system where different menus are presented according to the skin color of a guest remains largely unheard of in China. Most restaurants only have one menu—the Chinese one. Learning some Chinese characters such as beef (牛), pork (猪), chicken (鸡), fish (鱼), stir-fried (炒), deep-fried (炸), braised (烧), baked or grilled (烤), soup (汤), rice (饭), or noodles (面) will take you a long way. As pork is the most common meat in Chinese cuisine, where a dish simply lists "meat" (肉), assume it is pork.

Dishes ordered in a restaurant are meant for sharing amongst the whole party. If one person is treating the rest, they usually take the initiative and order for everyone. In other cases, everyone in the party may recommend a dish. If you are with Chinese people, it is good manners to let them choose, but also fine to let them know your preferences.

If you are picking the dishes, the first question to consider is whether you want rice. Usually you do, because it helps to keep your bill manageable. However, real luxury lies in omitting the rice, and it can also be nice when you want to sample a lot of the dishes. Rice must usually be ordered separately and won’t be served if you don’t order it. It is not free but very cheap, just a few yuan a bowl.

For the dishes, if you are eating rice, the rule of thumb is to order at least as many dishes as there are people. Serving sizes differ from restaurant to restaurant. You can never go wrong with an extra plate of green vegetables; after that, use your judgment, look what other people are getting, or ask the waiter how big the servings are. If you are not eating rice, add dishes accordingly. If you are unsure, you can ask the waiter if they think you ordered enough (你觉得够吗? nǐ juéde gòu ma?).

You can order dishes simply by pointing at them in the menu, saying “this one” (这个 zhè ge). The way to order rice is to say how many bowls of rice you want (usually one per person): X碗米饭 (X wǎn mǐfàn), where X is yì, liǎng, sān, sì, etc. The waiter will repeat your order for your confirmation.

If you want to leave, call the waiter by shouting 服务员 (fúwùyuán), and ask for the bill (买单 mǎidān).

Eating alone

Traditional Chinese dining is made for groups, with lots of shared dishes on the table. This can make for a lonely experience and some restaurants might not know how to serve a single customer. It might however provide the right motivation to find other people (locals or fellow travellers) to eat with! But if you find yourself hungry and on your own, here are some tips:

Chinese-style fast food chains provide a good option for the lone traveller to get filled, and still eat Chinese style instead of western burgers. They usually have picture menus or picture displays above the counter, and offer set deals (套餐 tàocān) that are designed for eating alone. Usually, you receive a number, which is called out (in Chinese) when your dish is ready. Just wait at the area where the food is handed out – there will be a receipt or something on your tray stating your number. The price you pay for this convenience is that ingredients are not particularly fresh. It’s impossible to list all of the chains, and there is some regional variation, but you will generally recognize a store by a colourful, branded signboard. If you can’t find any, look around major train stations or in shopping areas. Department stores and shopping malls also generally have chain restaurants.

A tastier and cheaper way of eating on your own is street food, but exercise some caution regarding hygiene, and be aware that the quality of the ingredients (especially meat) at some stalls may be suspect. That said, as Chinese gourmands place an emphasis on freshness, there are also stalls that only use fresh ingredients to prepare their dishes if you know where to find them. Ask around and check the local wiki page to find out where to get street food in your city; often, there are snack streets or night markets full of stalls. If you can understand Chinese, food vlogs are very popular on Chinese social media, so those are a good option for finding fresh and tasty street food. Another food that can be consumed solo are noodle soups such as beef noodles (牛肉面 niúròumiàn), a dish that is ubiquitous in China and can also be found at many chain stores.

Even if it may be unusual to eat at a restaurant alone, you will not be thrown out and the staff will certainly try to suggest something for you.

Dietary restrictions

All about MSG Chinese food is sometimes negatively associated with its use of MSG. Should you be worried? 전혀. MSG, 또는 monosodium glutamate, is a simple derivative of glutamic acid, an abundant amino acid that almost all living beings use. Just as adding sugar to a dish makes it sweeter and adding salt makes it saltier, adding MSG to a dish makes it more umami, or savory. Many natural foods have high amounts of glutamic acid, especially protein-rich foods like meat, eggs, poultry, sharp cheeses (especially Parmesan), and fish, as well as mushrooms, tomatoes, and seaweed. First isolated in 1908, within a few decades MSG became an additive in many foods such as dehydrated meat stock (bouillon cubes), sauces, ramen, and savory snacks, and a common ingredient in East Asian restaurants and home kitchens. Despite the widespread presence of glutamates and MSG in many common foods, a few Westerners believe they suffer from what they call "Chinese restaurant syndrome", a vague collection of symptoms that includes absurdities like "numbness at the back of the neck, gradually radiating to both arms and the back", which they blame on the MSG added to Chinese food. This is bunk. It's not even possible to be allergic to glutamates or MSG, and no study has found a shred of evidence linking the eating of MSG or Chinese food to any such symptoms. If anyone has suffered these symptoms, it's probably psychological. As food critic Jeffrey Steingarten said, "If MSG is a problem, why doesn't everyone in China have a headache?" Put any thoughts about MSG out of your mind, and enjoy the food. |

People with dietary restrictions will have a hard time in China.

Halal food is hard to find outside areas with a significant Muslim population, but look for Lanzhou noodle (兰州拉面, Lánzhōu lāmiàn) restaurants, which may have a sign advertising "halal" in Arabic (حلال) or Chinese (清真 qīngzhēn).

Kosher food is virtually unknown, and pork is widely used in Chinese cooking (though restaurants can sometimes leave it out or substitute beef). Some major cities have a Chabad or other Jewish center which can provide kosher food or at least advice on finding it, though in the former case you'll probably have to make arrangements well in advance.

Specifically Hindu restaurants are virtually non-existent, though avoiding beef is straightforward, particularly if you can speak some Chinese, and there are plenty of other meat options to choose from.

For strict vegetarians, China may be a challenge, especially if you can't communicate very well in Chinese. You may discover that your noodle soup was made with meat broth, your hot pot was cooked in the same broth as everyone else's, or your stir-fried eggplant has tiny chunks of meat mixed in. If you're a little flexible or speak some Chinese, though, that goes a long way. Meat-based broths and sauces or small amounts of ground pork are common, even in otherwise vegetarian dishes, so always ask. Vegetable and tofu dishes are plentiful in Chinese cuisine, and noodles and rice are important staples. Most restaurants do have vegetable dishes—the challenge is to get past the language barrier to confirm that there isn't meat mixed in with the vegetables. Look for the character 素 sù, approximately meaning "vegetarian", especially in combinations like 素菜 sùcài ("vegetable dish"), 素食 sùshí ("vegetarian food"), and 素面 ("noodles with vegetables"). Buddhist restaurants (discussed above) are a delicious choice, as are hot pot places (though many use shared broth). One thing to watch out for, especially at hot pot, is "fish tofu" (鱼豆腐 yúdòufǔ), which can be hard to distinguish from actual tofu (豆腐 dòufǔ) without asking. As traditional Chinese cuisine does not make use of dairy products, non-dessert vegetarian food is almost always vegan. However, ensure that your dish does not contain eggs.

Awareness of food allergies (食物过敏 shíwù guòmǐn) is limited in China. If you can speak some Chinese, staff can usually answer whether food contains ingredients like peanuts or peanut oil, but asking for a dish to be prepared without the offending ingredient is unlikely to work. When in doubt, order something else. Szechuan peppercorn (花椒 huājiāo), used in Szechuan cuisine to produce its signature málà (麻辣) flavor, causes a tingly numbing sensation that can mask the onset of allergies, so you may want to avoid it, or wait longer after your first taste to decide if a dish is safe. Packaged food must be labeled if it contains milk, eggs, fish, shellfish, peanuts, tree nuts, wheat, or soy (the same as the U.S., likely due to how much food China exports there).

A serious soy (大豆 dàdòu) allergy is largely incompatible with Chinese food, as soy sauce (酱油 jiàngyóu) is used in many Chinese dishes. Keeping a strictgluten-free (不含麸质的 bùhán fūzhì de) diet while eating out is also close to impossible, as most common brands of soy sauce contain wheat; gluten-free products are not available except in expensive supermarkets targeted towards Western expatriates. If you can tolerate a small amount of gluten, you should be able to manage, especially in the south where there's more emphasis on rice and less on wheat. Peanuts (花生 huāshēng) and other nuts are easily noticed in some foods, but may be hidden inside bread, cookies, and desserts. Peanut oil (花生油 huāshēngyóu) 및 sesame oil (麻油 máyóu or 芝麻油 zhīmayóu) are widely used for cooking, seasoning, and making flavored oils like chili oil, although they are usually highly refined and may be safe depending on the severity of your allergy. With the exception of the cuisines of some ethnic minorities such as the Uyghurs, Tibetans and Mongols, dairy is uncommon in Chinese cuisine, so lactose intolerant people should not have a problem unless you are travelling to ethnic-minority areas.

Respect

There's a stereotype that Chinese cuisine has no taboos and Chinese people will eat anything that moves, but a more accurate description is that food taboos vary by region, and people from one part of China may be grossed out by something that people in another province eat. Cantonese cuisine in particular has a reputation for including all sorts of animal species, including those considered exotic in most other countries or other parts of China. That said, the cuisine of Hong Kong and Macau, while also Cantonese, has somewhat more taboos than its mainland Chinese counterpart as a result of stronger Western influences; dog and cat meat, for instance, are illegal in Hong Kong and Macau.

에 이슬람교도 communities, pork is taboo, while attitudes towards alcohol vary widely.

Etiquette

Table manners vary greatly depending on social class, but in general, while speaking loudly is common in cheap streetside eateries, guests are generally expected to behave in a more reserved manner when dining in more upmarket establishments. When eating in a group setting, it is generally impolite to pick up your utensils before the oldest or most senior person at the table has started eating.

China is the birthplace of chopsticks and unsurprisingly, much important etiquette relates to the use of chopsticks. While the Chinese are generally tolerant about table manners, you will most likely be seen as ill-mannered, annoying or offensive when using chopsticks in improper ways. Stick to the following rules:

- Communal chopsticks (公筷) are not always provided, so diners typically use their own chopsticks to transfer food to their bowl. While many foreigners consider this unhygienic, it is usually safe. It is acceptable to request communal chopsticks from the restaurant, although you may offend your host if you have been invited out.

- Once you pick a piece, you are obliged to take it. Don't put it back. Confucius says never leave someone with what you don't want.

- When someone is picking from a dish, don't try to cross over or go underneath their arms to pick from a dish further away. Wait until they finish picking.

- In most cases, a dish is not supposed to be picked simultaneously by more than one person. Don't try to compete with anyone to pick a piece from the same dish.

- Don't put your chopsticks vertically into your bowl of rice as it is reminiscent of incense sticks burning at the temple and carries the connotation of wishing death for those around you. Instead, place them across your bowl or on the chopstick rest, if provided.

- Don't drum your bowl or other dishware with chopsticks. Only beggars do it. People don't find it funny even if you're willing to satirically call yourself a beggar. Likewise, don't repeatedly tap your chopsticks against each other.

Other less important dining rules include:

- Whittling disposable chopsticks implies you think the restaurant is cheap. Avoid this at any but the lowest-end places, and even there, be discreet.

- Licking your chopsticks is considered low-class. Take a bite of your rice instead.

- All dishes are shared, similar to "family style" dining in North America. When you order anything, it's not just for you, it's for everyone. You're expected to consult others before you order a dish. You will usually be asked if there is anything you don't eat, although being overly picky is seen as annoying.

- Serve others before yourself, when it comes to things like rice and beverages that need to be served to everyone. 예를 들어 자신에게 두 번째 밥을 대접하고 싶다면 먼저 다른 사람이 부족한지 확인하고 먼저 대접하겠다고 제안하십시오.

- 식사할 때 후루룩 소리를 내는 것은 흔한 일이지만 특히 교육을 많이 받은 가정에서는 부적절한 것으로 간주될 수 있습니다. 그러나 일부 미식가들은 차를 시음할 때 "커핑(cupping)"하는 것과 같은 후루룩을 맛을 향상시키는 방법으로 간주합니다.

- 호스트나 안주인이 접시에 음식을 올려놓는 것은 정상입니다. 친절과 환대의 몸짓입니다. 거절하고 싶다면 기분이 상하지 않도록 하십시오. 예를 들어, 당신은 그들이 먹고 당신이 스스로 봉사하도록 주장해야 합니다.

- 많은 여행 책에 따르면 접시를 청소하는 것은 호스트가 음식을 잘 먹지 못했고 더 많은 음식을 주문해야 한다는 압박감을 느낄 것임을 암시합니다. 실제로 이것은 지역에 따라 다르며 일반적으로 식사를 마치려면 섬세한 균형이 필요합니다. 접시를 청소하면 일반적으로 더 많은 음식이 제공되지만 너무 많이 남기는 것은 마음에 들지 않는다는 신호일 수 있습니다.

- 숟가락은 수프를 마시거나 죽과 같이 묽거나 물기가 많은 음식을 먹을 때 사용하며 때로는 서빙 접시에 담아 내기도 합니다. 숟가락이 없으면 그릇에서 직접 수프를 마셔도 좋습니다.

- 핑거 푸드는 레스토랑에서 흔하지 않습니다. 일반적으로 젓가락 및/또는 숟가락으로 먹어야 합니다. 손으로 먹어야 하는 희귀식품의 경우 일회용 비닐장갑이 제공될 수 있습니다.

- 조각이 너무 미끄러워서 가져갈 수 없으면 숟가락을 사용하여 수행하십시오. 날카로운 젓가락으로 찌르지 마세요.

- 생선 머리는 진미로 간주되어 귀하에게 영예로운 손님으로 제공될 수 있습니다. 사실, 일부 물고기 종의 볼살은 특히 맛있습니다.

- 테이블에 게으른 수잔이 있는 경우 게으른 수잔을 회전시키기 전에 아무도 음식을 잡고 있지 않은지 확인하십시오. 또한 게으른 수잔을 돌리기 전에 게으른 수잔에게 너무 가까이 놓았을 수 있는 다른 사람의 찻잔이나 젓가락이 접시에 떨어지지 않는지 확인하십시오.

대부분의 중국인들은 찐 밥 한그릇에 간장을 넣지 않습니다. 사실 간장은 주로 요리 재료이고 때로는 조미료로 사용되기 때문에 식당에서 사용조차 할 수 없는 경우가 많습니다. 밥은 고소한 맛이 나는 요리와 대조를 이루며 전분으로 식사를 풍성하게 하기 위해 평범한 면으로 사용됩니다.

누가 청구서를 지불합니까?

중국에서 레스토랑과 술집은 매우 흔한 유흥 장소이며 대접은 사교에서 중요한 역할을 합니다.

법안을 분할하는 것이 젊은이들에게 받아들여지기 시작하는 동안 대우는 여전히 표준입니다. 특히 당사자가 분명히 다른 사회 계층에 있을 때 그렇습니다. 남자는 여자를, 장로에서 후배, 부자에서 가난한 자, 호스트를 손님으로, 노동계급을 비소득계급(학생)으로 대우해야 합니다. 같은 반 친구들은 일반적으로 "이번은 내 차례이고 다음에는 처리합니다."와 같이 청구서를 분할하는 것보다 지불할 기회를 분할하는 것을 선호합니다.

중국인들이 비용을 지불하기 위해 치열하게 경쟁하는 것을 보는 것은 일반적입니다. 당신은 반격을 하고 "내 차례야, 다음 번에 나를 대할 거야"라고 말해야 합니다. 웃는 패자는 승자가 너무 예의 바르다고 비난할 것이다. 이 모든 드라마는 여전히 모든 세대에 공통적이며 일반적으로 진심으로 연주되었음에도 불구하고 젊은 도시 중국인들 사이에서 다소 덜 널리 실행되고 있습니다. 중국인과 함께 식사할 때마다 치료를 받을 수 있는 공정한 기회가 있을 것입니다. 저예산 여행자에게 좋은 소식은 중국인들이 외국인을 대하는 데 열심인 경향이 있다는 것입니다. 하지만 학생과 일반 노동자 계층에게 많은 것을 기대해서는 안 됩니다.

즉, 중국인은 외국인에 대해 매우 관대한 경향이 있습니다. 네덜란드에 가고 싶다면 시도해보십시오. 그들은 "모든 외국인은 네덜란드를 선호한다"고 믿는 경향이 있습니다. 그들이 논쟁을 벌이려 한다면, 그것은 일반적으로 그들이 당신의 청구서에 대한 지불을 주장하지만 그 반대가 아님을 의미합니다.

팁 일부 레스토랑은 청구서에 커버 차지, 서비스 차지 또는 "차 요금"을 추가하지만 중국에서는 실행되지 않습니다. 팁을 남기려고 하면 "잊은" 돈을 반환하기 위해 서버가 실행될 수 있습니다.